The following article is courtesy of Nadia Hussein, originally published on her blog Us Ordinary People.

I’ve been interested in learning more about the Karen people from Burma ever since my adopted parents, Michael Shafer and Evelind Schecter, established a nonprofit called Warm Heart Worldwide that works primarily with Karen people in Northern Thailand. The Karen (pronounced kah-REN) are a minority group that has faced and continues to face intense political oppression from the Burmese military government, causing many of them to escape to the Thai/Burma border as refugees. The border has thousands of Karen who populate several different camps along the border.

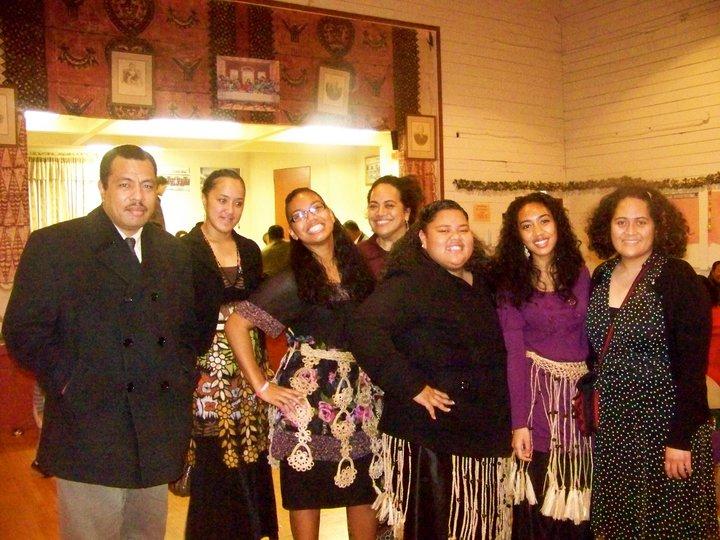

Bebe is a young Karen woman whom I met in Oakland. After we met, she invited me to her church to learn more about the Karen community here. As Bebe took me through the halls of the church and introduced me to her family, I was a bit overwhelmed by how warm and open the people were around me. More than anything, however, I was interested in hearing Bebe’s story. I finally got the chance during lunch, where I had awesome Burmese and Thai food (for me one of the best parts of intercultural connecting is definitely the food!).

Bebe began by telling me about how her father first came to Thailand from Burma by accident. At sixteen years old, he and some friends crossed the border, then were not allowed back in. He left his old life behind without his family having any clue about his whereabouts. Later, he and Bebe’s mother met at the Thai/Burma border and Bebe was subsequently born in the Mae La refugee camp in Thailand. The Mae La camp was set up by the United Nations and is the largest refugee camp in Thailand, with over 45,000 Burmese refugees. Bebe explained how in the camp, families received food every fifteen days, and would get donated clothes, mostly from Japan. When it came to housing, Bebe recalled how, unlike America where “you can live forever,” they had to build a house every year because the homes were made out of bamboo that had to be replaced due to damage caused by heavy rains. Bebe would climb on her house along with her mother to help rebuild. She also explained that the UN didn’t provide income for the refugees; they were just given food and a place to live. As a result, her parents worked in the fields to make money. Since there weren’t many jobs available outside the camp, people often worked in the fields planting vegetables. Generally though, there weren’t really jobs available on the outside, so most young people would work inside the camps after graduating high school. Bebe said that many young people would also marry early because they don’t know what else to do.

Bebe did attend school while in the camp; there were about 22 schools in her camp alone. The schools are not connected with the UN, though. Different schools had different sponsors and different connections. After hearing about her experiences in Mae La, I asked her if life was generally okay, since they did have many of the basic amenities. “No it’s not" she said "I’m telling you the truth, you don’t want to live like that. At night you just want to sleep and you want to go to school, if you walk one hour and a half or two hours you get to the border and theBurmese soldiers would shoot over. The camp was in a valley, and the soldiers would climb up in the mountains and shoot down.” She described how shells would get thrown in, and that one of her uncles got struck with shrapnel near his hip. One of her friends, who was thirteen at the time, also got hit and was unable to go to school for a very long time. "A lot of people have been hurt, some have no legs, hands, eyes, most Karen people you see are hurt like that," she said. The soldiers would also come into the camps, and sometimes burn down homes. "They came into the camp when they know that there are no people to fight them." Bebe recalled an incident when she was 5 or 6, where she was worshiping inside a church with many others while soldiers were walking through the camp. Everyone was quiet as the parishioners prayed, and the soldiers thought that no one was in the church due to the silence. I asked her if the UN did anything about soldiers coming into the camp or if there was any security. She said that when Thai soldiers in the area heard the gunshots, they would go to the hills and leave the people alone. "Camp is just Camp, there isn’t security, there is a fence and that’s it," she told me.

Bebe immigrated to the United States along with her father and two brothers in 2007. Her mother had to come separately with Bebe’s grandmother, who had been ill. When immigrating to other nations, refugees often have to satisfy strict criteria. These include things like health, or if someone is truthfully telling their story in order to leave the country. Bebe’s older sister also arrived separately since she was over 21, which is the legal age limit to file for refugee status on your own.

When Bebe came to the United States with her father and brothers, her family first received assistance from the Burmese Mission Baptist Church, the same church where I was interviewing her. She told me how they helped her and her family with clothes, and how they also got support from the IRC (International Rescue Committee). When she started school, she didn’t speak English. Luckily, she was enrolled in an international school in Oakland that had the resources to work with immigrant students by providing English language learning and translation.

Today, Bebe speaks great English, and is waiting to hear back from the colleges that she has applied to for next year. During her time in the US, she has had some amazing experiences, from attending a summer program in Boston, for which she was able to travel to the east coast for the first time, to kayaking and mountain climbing in Yosemite National Park. However, she still holds a very special place in her heart for her culture and her people. She hopes to find a way to go back to Thailand, to help the Karen there. As for Burma, Bebe says, “I really don’t want to go to Burma at all, because I heard that when people go there bad things happen." She relayed a story of one of her friends from the camp in Thailand whose father had been an opposition soldier a long time ago in Burma. He can never return to Burma or he will be killed, even though he has no involvement anymore as a soldier. "Even at the checkpoints, the only people who are allowed in are those who have connections or know the military".

In the end, Bebe said, “Everything is a blessing from God. My family spends time to come to church to give thanks, because if they look behind at their lifetime, things are so different. And if you live on the Thai border, you cannot open your eyes to see the world, to have good opportunities, to get good education and learn English."

When I asked Bebe if there was anything else she wanted people to know, she responded that she wants people to know that there are Karen people everywhere, with the largest group outside of Burma and Thailand being in America. There is a Karen New Year celebration every year, which is one of the few times when Karen people become somewhat visible. "Usually, people do not know who they are or their culture, but that it would be nice for people to know about Karen people," Bebe says. When she tells people that she is “Karen” they say “Korean?" because people have never heard of it before. "It is Karen, not Korean!" she exclaims, laughing.

As our interview ended, we had to rush out. We had been talking for so long that people had started folding the tables and chairs around us. As I said goodbye to her, I looked back on the two days I spent with Bebe at her church. It is truly an amazing experience to be welcomed into a space when you are an outsider and where a smile gets you so far even though you don’t know the language. It was a rare opportunity to be given an inside look into a culture that I had never been exposed to, and I was lucky to have had such a great guide.

Thank you, Bebe, for sharing your story with me. I know you will only go on to do more, and experience more amazing things in your life!